Where have all the medicines gone?

Drug shortages in South Africa’s health facilities have become a crisis. Today we report that Stanger Hospital and health facilities in Ilembe District KwaZulu-Natal are out of stock of over 200 products between them.

Stanger Hospital has a list of 30 drugs considered critical that are out of stock. These include various doses of morphine, some antibiotics and antiretrovirals, especially paediatric ones, used to treat HIV. About a hundred patients per week are going without ranitidine which prevents stomach ulcers. Several Ilembe facilities are even out of stock of paracetamol tablets.

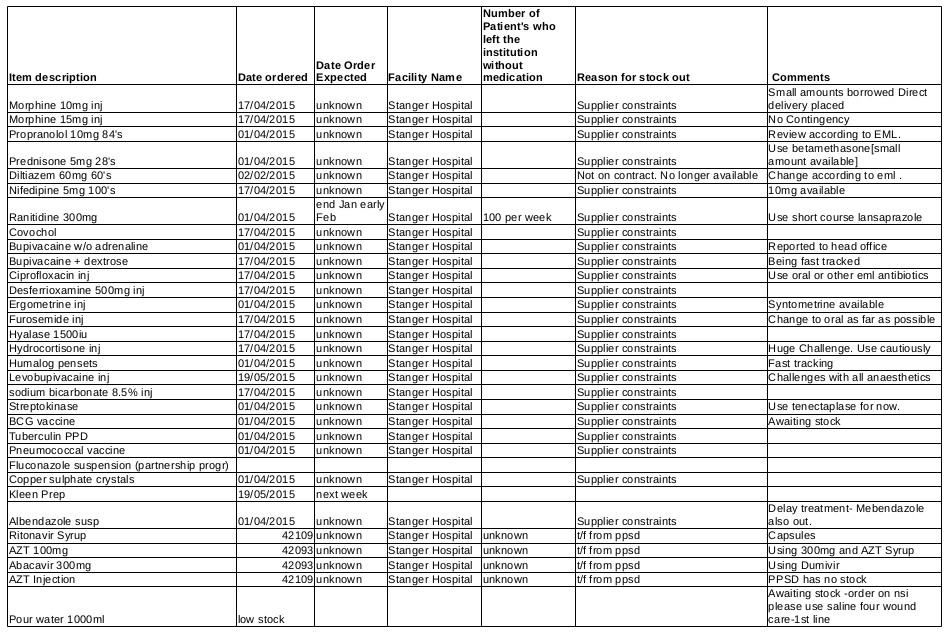

Two Microsoft Excel spreadsheets files have been given to GroundUp. The one contains a full list of stockouts. The other lists the most critical drugs that are unavailable. The sheets are divided into weeks going from August 2014 to May 2015, and they show that stockouts are an ongoing problem.

When phoned on Friday afternoon, Sam Mkhwanazi, the communications head in the KwaZulu-Natal health department, said that he was unaware of the stockouts in Ilembe District.

List of critical drugs out of stock at Stanger Hospital as taken from the last sheet (22-05-2015) in this Excel file. “t/f from ppsd” means To Follow from Provincial Pharmaceutical Supply Depot. Click the image to enlarge it in your browser.

Drug stockouts have been reported in the news frequently in South Africa for the past few years, and especially in the last few weeks. In May the Minister of Health, Aaron Motsoaledi, acknowledged that some drugs, such as the antiretroviral abacavir which is primarily needed to treat children with HIV, are out of stock, but the statement played down the problem and implied that to the extent that stockouts are occurring, it is a worldwide problem.

A statement by the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health on 19 May also acknowledged that the province is experiencing serious stockouts. It stated, “Regrettably, medicine shortages or stock-outs are of international concern, and medicines that are in short supply locally are also in short supply internationally.” It later says, “Urgent remedial activities with suppliers are underway to address the identified challenges.”

In an email to GroundUp, Dr Anban Pillay the Deputy Director-General of the National Department of Health, said that the problem can be seen in the US, Canada, Europe and Australia. In 2013 there was a summit held in Canada that addressed the issue of stock outs with a report being compiled that outlined recommendations. “We have benchmarked our practice against these recommendations so I can say that we have implemented global best practice to address the problem,” said Pillay.

It is true that there are worldwide drug stockout issues. It is also the case that the South African private sector is experiencing more drug stockouts than usual. However, the list of out-of-stock drugs in the Ilembe district that we have released today is evidence that the problem in the public health system is particularly serious.

Polly Clayden of HIV i-Base described an example of the seriousness of the problem with HIV medicines. One of the out-of-stock drugs in Stanger Hospital is ritonavir syrup. This drug is used to boost the level of an antiretroviral, lopinavir, in the body. Without it, not enough lopinavir is absorbed into the child’s bloodstream, which means the HIV might not be suppressed properly, with possible consequences for the child’s health. Older children taking syrups might be able to switch to pills. But babies and young children cannot swallow pills.

In Stanger Hospital the large number of unavailable drugs means that hospital staff are constantly scratching about for replacement drugs, trying to identify alternative treatment strategies and following up on stockouts.

And Ilembe District is not unique. The problem is countrywide. Several experts we spoke to said that the problem is less acute in Western Cape public facilities because the province has a well run drug supply chain. But even here there are shortages.

A health worker at Groote Schuur, speaking anonymously, told GroundUp that a number of important drugs had been out of stock, such as cloxacillin, an antibiotic. “It’s a common drug [that was] unavailable for a couple of weeks.” The health worker said it was not catastrophic because it can be substituted, “but the replacement might be more expensive or more broad spectrum with consequences for resistance,” he explained.

“A very basic drug we could not for a while get was intravenous sodium bicarbonate which is used for resuscitating some patients,” he said.

He also said there was a worldwide shortage of intravenous haloperidol, which is used to treating delirium. It can’t be taken orally by people who are critically ill. This too was out of stock at Groote Schuur, “but it’s back now.”

Mark van der Heever, who is the Deputy Director of Communications in the Western Cape Department of Health, said that the province has been “managing the situation pro-actively.” He said, “We have been moving smaller quantities of stock around, dispensing smaller quantities and offering alternatives where possible. The department has also negotiated with pharmaceutical companies to supply certain medication off contract, where possible.”

Van der Heever said that the Western Cape Department had not had any situations where an individual with a life-threatening or serious condition could not be treated. “The situation is slowly returning to normal and in most cases stock levels are sufficient to supply patients with required medication without any inconvenience,” said van der Heever.

The problem has not been limited to the public sector. Allan Freedberg of Sunset Pharmacy in Sea Point, Cape Town, said that stockouts are a problem for a range of drugs. Recently the pharmacy has been unable to access propranolol hydrochloride which is used to treat hypertension, lorazepam used to treat anxiety, and the 20mg dose of atorvastatin which is used to lower cholesterol, among other drugs. “Nine times out of ten there are other options. It has not reached critical stage. It is more an inconvenience,” said Freedberg. “We never get the true story, sometimes they say it’s due to sourcing, sometimes quality.”

Why are stockouts happening?

Andy Gray is a senior lecturer of pharmacy at the University of KwaZulu-Natal and an expert on the pharmaceutical industry. He explained that there are multiple reasons for the drug stockouts. “The national department is very aware of the issue, and is leaning hard on suppliers. Some of the problems are global in nature, for example reduced access to some active pharmaceutical ingredients [the main ingredient in the finished drug product] on the global market. In essence, there is a global problem with access to old, off-patent products where the price is getting very close to the cost of production. Firms are abandoning such markets and seeking higher return alternatives.”

Aspen Pharmacare is the country’s biggest generic pharmaceutical company. Senior executive of strategic trade development, Stavros Nicolaou, said that the issue of stockouts is multifactorial. Nicolaou said that a big issue is the unavailability of the active pharmaceutical ingredients. “There has been a deficit of some of the key drugs and in some cases a complete non-supply,” he said.

Nicolaou said that Aspen tries to mitigate the effects of stockouts as much as possible. He said that they try to stick to local companies to supply them because when the supply is under pressure a local company will be more likely to prioritise the domestic market.

A further problem is that suppliers of active pharmaceutical ingredients might prioritise selling to US and European markets where they can fetch higher prices.

The global problems don’t explain the high level of stockouts being seen in the public health system, or the fact that it is less of a problem in the Western Cape than elsewhere.

An industry insider who asked to remain anonymous told GroundUp, “The pharmaceutical industry is not blameless. Some companies are less reliable than others. Sometimes it is to do with tendering.” He explained that companies will tender at low prices to get a government contract to supply most of the units of a particular medicine. They then get awarded too many units, which they don’t have the capacity to produce.

He also explained that there are problems sourcing the active pharmaceutical ingredients, which are manufactured mostly in India and China, where there are “ongoing quality issues”.

The insider explained that the department awards multiple companies to supply drugs in case one can’t fill orders. But “if a company … falls behind, then [this puts] pressure on the other companies.” Sometimes the price at which the active ingredients or even the finished product are imported rises above the price agreed to on tender.

The health department’s systems are a further reason for stockouts. “Sometimes the tenders are awarded very late, even after the tender period has started,” said the insider, and this causes backlogs. The suppliers “can’t deal with panic ordering.”

The insider also confirmed that there are occasional shenanigans in the tendering system. “Sometimes companies are being awarded the product but they don’t have the infrastructure to supply the country. Or they don’t have cash flow.”

The insider explained that at provincial level problems arise with the forecasting of stock. Stockouts occur when a province orders more than it originally estimated. “Further problems arise over late supplier payment and subsequent withholding of stock,” he said. “The Western Cape is seen to be in a much better position than other provinces due to specific systems being in place to regulate the supply chain.”

Marcus Low, director of policy for the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), laid most of the blame with state dysfunction. “Based on the evidence at our disposal, the majority of medicine stockouts in the public sector are not because of supply shortages, but because of distribution problems in the public system. Clinics don’t order in time or enough, depots often do not deliver in time, and so on. We seem to lack the management skills to ensure effective distribution. We see these kinds of stockouts as a symptom of the wider dysfunction in our public health system. In our view this is partly driven by the ruling party’s policy of cadre deployment.”

TAC has also collected a list of stockouts which the organisation will publish shortly. It has recorded stockouts of essential medicines in all seven provinces where the organisation is active.

Stop Stock Outs is a joint project of several organisations. It stated, “There is no oversight of the depot to check why a clinic didn’t order this month, or why they ordered so erratically or ordered insufficient stock.” The project also claimed that most delivery is outsourced and that poor management of the delivery company causes stockouts.

The national department’s Anban Pillay acknowledged that there are problems at provincial level: “At depot or wholesaler level it is usually poor forecast planning, logistical failures, poor inventory management and account payments.” He said the national department has been implementing a number of interventions to support provinces. These include using cell phones to track stockouts, the implementation of a pharmacy management tool, central stockout reporting, a protocol for resolving stockouts at provincial level and training.

However, if the TAC’s diagnosis of the problem is correct — that cadre deployment is at least partially responsible for the dysfunctional health system — fixing the stockout problem will likely require more than just technical changes.

Disclosure: Nathan Geffen used to be with the Treatment Action Campaign. He no longer holds any position with the organisation.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.