Hani’s murder: an attempt to assassinate a country’s future

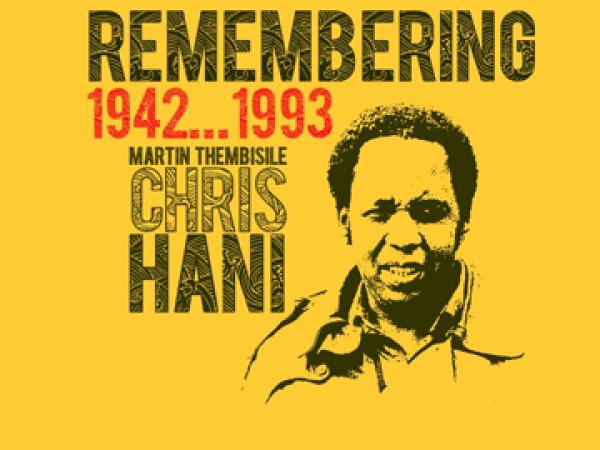

10 April marks the 21st anniversary of Chris Hani’s murder. His death left a nation wondering what its future would have been like had he lived.

Martin Tembisile was born in the rural Transkei town of Cofimvaba in 1942. When he returned for the first time after 40 years, he found little changed in this isolated dorp, exposed to the elements, on an important but potholed road linking the N2 and the N6, Umtata and Queenstown.

He grew up a shepherd and cattle herder. His father was away working on the Transvaal mines. A quiet child, who liked to read while he sucked his thumb; read so much it produced a malocclusion.

To get to school he’d walk; walk two hours home each day. He came top of the district in primary school.

Every morning, right up to the day he died, he ran on an empty stomach, ran as much as ten kilometres. He rarely ate breakfast; preferred tea.

On Sundays, as a devout altar boy, he enjoyed the mystery of the ceremonies and the secrecy of the Catholic Fathers; with their confessional and its introspection; their code of selfless service; and their dedication to the poor. It was the example they set, not their beliefs that gave him conviction.

He developed an abiding love of Latin and the Classics; would name his eldest daughter, Cleopatra, and her son, Aluta. The action of tyrants as portrayed in various literary works “also made me hate tyranny and institutionalised oppression”.

His Catholicism ended when he asked, “What is this God doing about the suffering of my people?”

Faith in Christ lost out to confidence in Marx. And Lenin.

“I understand religion better than I did when I was most at home within it. Religion is just another philosophy.”

He could see the poor getting poorer before his eyes. Taxes were raised, people forcibly removed. Drought struck, and stock were culled. Three of his siblings died in infancy.

Lovedale School had a rigorous regimen. The boys showered naked outdoors in all weather and all seasons; it can snow in these parts.

The introduction of Bantu Education by the apartheid regime sends him searching. He seeks out Communists. Still a boy, his first mission is to dispose by fire of the clothes of an enemy agent.

Revolutionary activity runs in the family. One day, he will join his father, first as a fellow political activist in Cape Town, and then again in Lesotho, where his father is banished by the Transkei puppet regime of Matanzima.

His father sacrifices all he can to put him through Fort Hare University College. But the graduation ceremony is held at Rhodes, and his parents may not attend as it is in a WHITES ONLY auditorium.

The Treason Trial has convinced him to support the ANC.

The graduate is arrested in Cape Town with pamphlets. He escapes. He narrowly avoids re-arrest by pulling a small child on to his lap on a train the police are searching.

But they pick him up in Lusaka. Not for long. Colluding with a clerk of the court, he manages to dodge the authorities one more time.

Onward to the Soviet Union in 1962. As his nom de guerre, he takes the name of his younger brother Chris – Chris from Christ. He has developed into a thickset, tall and charismatic man. He sees Moscow through tinted spectacles. Here there are no homeless people; there is free health, and free education. The West has been lying about this country, a big imperialist lie. He wants to bring these things to his people.

In the 1960s, Comrade Hani is dispatched to the malaria-infested malaise of the Kongwa Camp in Tanzania. Conditions are extremely primitive. He likes to escape into the forest with his beloved Greek classics. He starts teaching the adult cadres literacy. Like his old priests, he becomes a confidant to the soldiers.

They tire of shooting paper targets. They want to infiltrate South Africa.

“Nobody must tell us there are no routes. Let us hack our way through these countries.”

They are sent on a suicide mission to prove themselves.His Luthuli Detachment has ambitions of carving out via Rhodesia a Ho Chi Minh trail of their own. The Wankie Campaign is an operational catastrophe: poorly planned, badly provisioned, short on ammunition, and armed with maps from the 1940s. It starts with an accidental shot going off, alerting their enemy.

Comrade Chris sets the pace, marching through the night. They eventually cover 200 kilometres to find themselves dehydrated and snagged in thick acacia thorn. In the skirmishes with the Rhodesian army he takes no prisoners. But the Rhodesians have spotter planes and air support. It turns to disaster for nearly all the individual soldiers, most of them killed, the rest captured.

The handful of survivors after 18 months in a Botswana jail, receive no debriefing, no inquiry into their experiences. But for the ANC it is a global publicity coup, a victory for morale.

Comrade Hani settles in Lusaka. Some feel embittered and left to rot. Hani is the leader of a group of eight who sense the revolution is being betrayed by an ANC living in exile, something that has become an end unto itself.

He pens a harsh memorandum criticising the leadership. The movement, he says, is mired in careerism, nepotism, business interests, globetrotting, and salaried professional politicians. People are named, including one Thabo Mbeki. He complains of “criminal and inhuman” treatment in the ANC camps, of torture and men dumped in pools of water in dugouts for three weeks.

Such criticism is taken as an act of treason. The group of eight are sentenced to death by tribunal, spared only by intervention at the highest level. He is suspended from the party. Don’t they understand? “Armed struggle is the mobiliser, the inspirer?”

Comrade Hani is “rehabilitated”.

He moves to ‘The Island’, as Lesotho is dubbed, joining his father. He flits in and out of the mountain kingdom, building cells as he was taught to do in the USSR. He is detained in Maseru: 90 days of solitary confinement and torture.

Oliver Tambo himself has to get him sprung by exerting influence on governing Chief Leabua Jonathan. Later, Hani strongly objects to donations made by the Lesotho military junta to the ANC.

Limpho née Sekemane, Hani’s wife, is arrested. They torture her brutally. She loses their first baby.

Hani is a father figure, mentor and hero to the generation of the ’76 uprising, clattering about in his VW Beetle, smuggling weapons under cover of freshly dug graves in cemeteries on the outskirts of town.

From their house, called Moscow, together with his wife, they guide the refugees to Swaziland. He chooses protégés. He is guarded by a pack of dogs. Several of them are poisoned. The hit squads are out to get him. The assassins botch it more than once. One would-be assassin blows himself up while planting a bomb on the car. He survives the massacre of 42 people by South African Special Forces.

The ANC camps are again in insurrection. The soldiers will only trust Hani. He is sent to sort it out. When he visits, he sleeps in the camp, not in the officers’ compound. He sits on the soldiers’ beds, tells jokes, eats beans and rice. He quells mutinies in the Angolan camps of Viana and Pango, convincing them to surrender peacefully. Afterwards, the men are dealt with brutally, to his shame.

On return to South Africa he will be the most popular leader after Mandela. What is more, South African Communist Party Secretary General Chris Hani not only has the township youth hotheads behind him, but strong rural support too, people drawn to his charisma and bonhomie.

But his elevated position makes him feel isolated. He wants to speak to the soldiers and to the ordinary people. Already in 1990 he warns: we cannot allow the AIDS epidemic to ruin the realisation of our dreams.

Thabo Mbeki is his arch rival. Walter Sisulu has to intercede at the ANC Congress in Durban, standing for election as Mandela’s second, against his own wishes, to avert a clash.

Hani is intolerant of drunks, but he likes his Molotov cocktails. Some of his rhetoric is incendiary. He invents the grenade squads. And he’s not averse to soft targets when, he says, “so many civilians are being targeted by the apartheid forces”. The leadership is squeamish.

It is Comrade Hani who has the power to suspend the armed struggle. In February 1991, he says it is the right thing to do. After so many attempts on his life he has a premonition and chooses a grave site.

He’d been out to buy the Saturday newspapers. He was still in his tracksuit. He wasn’t carrying his signature leather pouch with his Makarov pistol in it.

10 April 1993, Easter weekend: he’d booked security off that day. Hani was gunned down in the driveway of his modest house in the white Boksburg suburb of Dawn Park. The assassin fired, then shot him three more times at point-blank range through the head. His 15-year-old daughter, Nomakhwesi, saw it all.

Retha Harmse, Hani’s Afrikaans neighbour took down the killer’s licence plate. The assassin and his accomplices were rounded up shortly afterwards.

“A watershed moment for all of us,” said Mandela, that could “plunge our country into another Angola.”

Hani was 50 years old.

His death at the eleventh hour propelled the apartheid regime to hastily fix a date for the first democratic election.

In the days before he was gunned down, Chris Hani had made an impassioned speech for peace. He said he was prepared to lay down his life for the freedom of his country. And he did. He left a nation wondering what its future would have been like had he lived. His children write a letter to their father. They place it in the coffin.

This is an extract from ‘Five Lives at Noon’ published by Missing Ink (2013). Copyright: Brent Meersman

Next: Metrorail warns commuters in attempt to stop deaths on its network

Previous: The Two Halves of Cosatu

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.