South Africa should learn from Brazil’s Bolsa Familia

BRICS has come and gone. It has been driven from the headlines by Jacob Zuma using the hopes and aspirations of the millions who vote for the ANC as a means to enrich his narrow circle of crony capitalists through misuse of the SANDF in the Central African Republic. But before the memory of BRICS fades, let’s remember the B in BRICS is for Brazil, a country with which South Africa is often compared.

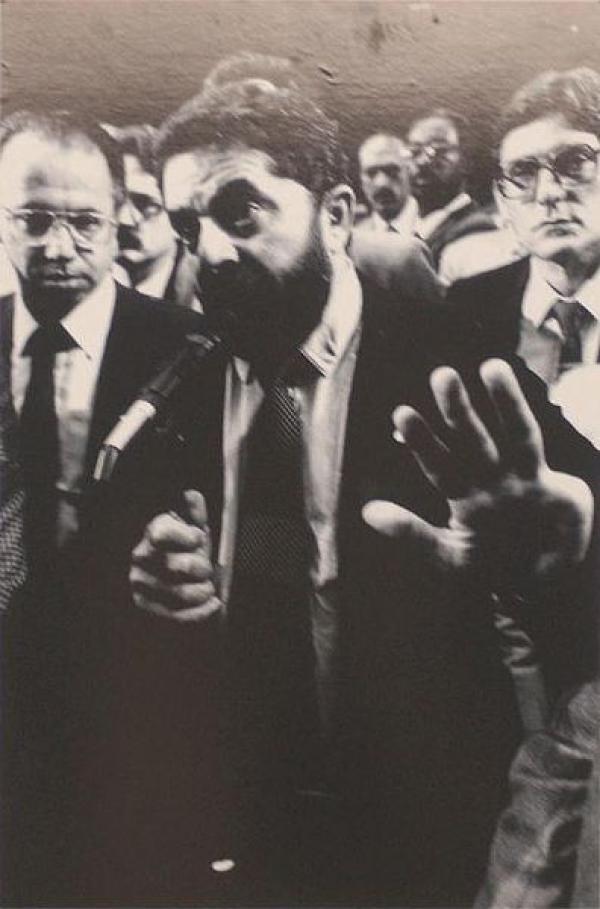

What can we learn from the great decrease in unemployment in Brazil from an all time high of 13% in 2003 to a low of 4.6% in December of 2012 and the increasing standards of living over the last ten years under the government of Lula De Saliva and the Workers Party? There is one overriding lesson: income redistribution by means of conditional cash transfers works! And the sooner we in South Africa devise ways to follow this example, the better. The key measure for lowering income inequality in Brazil that should be adopted immediately in South Africa is the Basic Income Grant.

In 2003 the Basic Income Grant Coalition—COSATU, the SA Council of Churches and the Black Sash—proposed R120 per person as the amount needed to secure the basic necessities. Because each member of a family would receive the grant, this would amount to R600 in an average poor household of 5 people. This is a helpful amount to pay for food, transport, school and other necessities. Today, allowing for inflation, the BIG amount should be about R170 per month. This should be in addition to any existing grant payment such as child support grants.

What evidence is there that cash transfers will help unlock economic growth?

A 2011 report by the International Monetary Fund found a strong association between first achieving lower levels of inequality and sustained periods of economic growth. That reverses the order of traditional trickle-down economics which proposes more concessions to the rich to eventually produce crumbs for the poor. Today this dogmatic trickle-down argument still holds the Obama Administration hostage to the Bush tax cuts for the rich. Developing countries such as Brazil have succeeded in initiating higher growth rates through promoting greater equality in income distribution. How did Brazil do it?

Lula da Silva, the former President of Brazil, introduced Bolsa Familia, a conditional cash grant for poor families in 2003. Bolsa Familia is the largest social grant scheme in the world. The programme is credited for lifting 20 million people out of poverty in a relatively short period of time. Bolsa Familia is a cash grant in exchange for families sending their kids to school and participating in other associated development support measures such as vaccinations, nutritional monitoring, prenatal and post-natal tests. The family unit as a whole is made accountable for ensuring that the development obligations, which the scheme requires, are being met. In exchange the Bolsa Familia costs the state about US$4.5 billion per year.

The result has been greater school attendance, less hunger, less social stress of all kinds (including gender abuse). Above all, it has created higher economic growth through greater demand for food, clothing, housing and things associated with that. It has simulated growth and employment in the basic industries: construction, textiles, consumer goods and agriculture. Why have we in South Africa not followed this example?

The short answer. Because the ANC was too timid to challenge big capital on this one. Although COSATU supported the Basic Income Grant, it was never a serious focus of the trade union movement because, I suspect, COSATU represents blue and white collar workers who would not be the main beneficiaries of the grant and would have had to pay something towards it. The DA used to support it (which probably did the cause of BIG more harm than good) but has let it slip off the radar in favor of the youth employment subsidy.

South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world, with a Gini coefficient of 0.7 in 2008. Since 1994 this standard measure of overall inequality has been moving in the wrong direction. The top 10% of the population accounted for 58% of South Africa’s income, a recent World Bank report said. The bottom 10% accounted for just 0.5% of income, and the bottom 50% less than 8%. The Bank hastened to point out that social grants already make up 70% of the income of the poorest 20% of South Africans. From this it concluded that social grants—conditional income transfers—were insufficient to create employment and that more social grants might not be a good thing. Of course a BIG on its own would not solve the structural unemployment problem in South Africa.

BIG would cost South Africa at today’s levels somewhere between R43 and R67 billion a year. This money could be raised by a small increase in the marginal tax rate for companies and wealthy individuals earning, say, over R1 million per year (something which is coming anyway - but let it go for the Basic Income Grant rather than military waste), an increase in VAT on luxury goods only, and, something which Brazil does to finance the Bolsa Familia, a tax on financial transactions. This latter tax is Brazil’s own “Tobin Tax” or “Robin Hood Tax”, set at 2% on speculative inflows of foreign funds (it doesn’t apply to investment in real production and services). There is no financial transaction tax in South Africa at present.

A Basic Income Grant, by shifting only a slightly greater proportion of national wealth to the poor would be an important stimulus to higher levels of economic activity. More money in the hands of the poor help improves the quality and quantity of health, education, housing, food supply, energy, electricity and transport. It creates employment and improves future growth prospects. Above all, the BIG would reduce stress and conflict in society. This is a critical consideration. It is widely agreed that the high levels of strike and protest action in South Africa make South Africa a less inviting place for both domestic and foreign direct investment.

The Basic Income Grant would not be sufficient to get employment levels up and reduce inequality. It is just one important measure among several that are needed. These include:

increased minimum wages linked to a campaign for a global minimum wage;

stable and lower cost energy prices with less dependence on imported oil;

large scale and properly regulated bio-fuels, gas (from the gas lake under the sea bed stretching from Mozambique to Namibia), wind, solar and the sale of Sasol oil from coal at cost +5% - equal to about $40 to $50 a barrel;

rational economic incentives and support for manufacturing including export zones where wage, electricity, re-location and factory building subsidies are available;

rational housing policy with consistent large scale production of higher density housing by large contractors who can mentor and sub-contract smaller black-owned contractors;

considering re-nationalisation of the steel producer Mittal and the sale of SA iron and steel at cost plus 5% on the domestic market to create a national competitive advantage;

greatly increasing the efficiency of the state by allowing state employment to decrease naturally, employing qualified experienced people from the population as a whole, ending cadre deployment and modifying (not ending) affirmative action (these policies are the handmaidens of crony capitalism, tender entrepreneurs and general corruption); and

mass literacy and numeracy campaigns both in schools and communities.

Come to think of it, this sounds very much like it could be the programme for a new political party!

Lewis is a farmer, political economist and the former director of Community Media Trust.

Next: Siyayinqoba Beat It!

Previous: The Real Threat to BC Today

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.