Debunking Jeremy Cronin on civil society

“Join our hands to fight the drug companies, join our hands to raise money from the private sector, join our hands in raising money from each of us who will contribute to save lives of everyone who needs to be saved.” With these words Zackie Achmat launched the Treatment Action Campaign in 1998.

But in a recent article 1 Jeremy Cronin, the Deputy General-Secretary of the SA Communist Party, narrowed the achievements of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) to the defeating of government denialism. Cronin praises TAC for this “exemplary role in mobilising ordinary South Africans in opposition to the appalling AIDS-denialism of the Mbeki administration”. Denialism was itself responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths,2 and TAC did lead the campaign that arrested this crime against humanity, but what Cronin ignores is that throughout its existence TAC campaigned extensively against private-sector criminality.

Cronin’s careful praise precedes the main accusation of his article, that TAC and its allies like Section27 (and possibly also the Social Justice Coalition, Equal Education and others?) “focus exclusively on bad government”.

Cronin says he is basing this assumption on an article by Mark Heywood,3 Director of Section27. But Heywood said nothing about “exclusively”.

The statement that launched TAC, then a campaign within the National Association of People Living with AIDS (NAPWA), read:

NAPWA has initiated the Treatment Action Campaign to draw attention to the unnecessary suffering and AIDS-related deaths of thousands of people in Africa, Asia and South America. These human rights violations are the result of poverty and the unaffordability of HIV/AIDS treatment.

TAC broke with NAPWA soon thereafter because NAPWA took money from the pharmaceutical industry, and would not openly challenge it. This was anathema to TAC which aimed to morally shame the drug companies into reducing medicines prices and permitting production of life-saving generic medicines.

It was the ANC government that was reticent to challenge the pharmaceutical industry, citing the high cost of medicines as one of its initial reasons for not providing treatment, and taking no measures, at the time, to make more affordable generic antiretrovirals available.

In 2000 TAC leader Christopher Moraka addressed Parliament’s health committee:

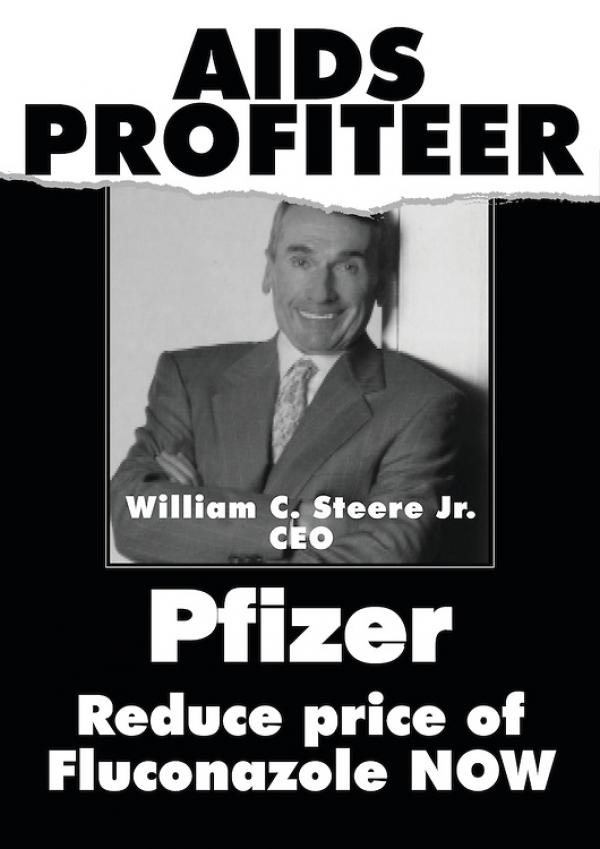

Companies like Pfizer make a lot of profit. In 1999 Pfizer made R6.5bn profit. We ask them to lower the price of drugs because we HIV-positive people suffer the most. Other people don’t feel this pain. They want to make profit, you see.

Pfizer was significant for Moraka personally. It had the patent on fluconazole, a medicine which Moraka needed. As Achmat explained at the same committee hearing:

Tonight in southern Africa at least 300 people will die because they cannot afford this. This is a drug called Diflucan [the commercial name for fluconazole]. It is a drug to stop people who have thrush, cryptococal meningitis, a range of AIDS-related illnesses, from dying. And this little bottle will cost you R500. Drug companies are trying to twist our government’s arm, to stop them from providing quality health care for all.

Christopher Moraka died in 2000 of AIDS-related opportunistic infections including systemic thrush. TAC then announced its Christopher Moraka Defiance Campaign against Patent Abuse and AIDS Profiteering. As part of this campaign TAC imported fluconazole from Thailand at a cost of R1.78 per capsule, at a time when it was selling for R29 per capsule in South Africa. Pfizer capitulated and began donating fluconazole to the public health system.

TAC then sided with government to defeat the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Association (PMA) and 40 multinational drug companies who challenged the provisions in the Medicines and Related Substances Control Amendment Act that allowed for generic substitution and importation. TAC organised worldwide demonstrations on 5 March 2001. Speaking outside the court Mazibuko Jara said: “Do not oppose our government and take it to court when it wants to meet our public health needs.”4 The PMA dropped their case on 19 April 2001.

The response of the health minister was to announce that anti-retrovirals would not be made available.

By 2002 the price of ARV treatment was still too high at R2,000 per month. TAC-member Hazel Tau brought a complaint to the Competition Commission against GlaxoSmithKline and Boehringer Ingelheim. In 2003 the Commission decided to proceed with the complaint and by December the companies had agreed to allow generic production. Today government pays just over R100 for a month’s supply of ARVs.

The tragedy of government’s denialism is that it followed all of this work. President Mbeki spent years blocking a comprehensive treatment plan, even after any financial argument had fallen away due to TAC’s work. Instead government shot rubber-coated bullets 5 at TAC demonstrators in Queenstown and embraced the most discredited fringes of the pharmaceutical industry; people like Matthias Rath, Tine van der Maas, Zeblon Gwala and Michelle and Zigi Visser.

Even after the defeat of denialism TAC and the AIDS Law Project continued to challenge the pharmaceutical industry, successfully bringing another complaint to the Competition Commission in 2007 against Abbott, MSD and Merck for refusing to license generic production of Lopinavir/Ritonavir, a crucial ARV treatment. Last year TAC, together with Section27, joined a court case against a multinational pharmaceutical company 6 that was denying access to a generic cancer drug.

The irony is that the ANC made TAC famous as the activists who defeated a President, whereas TAC came into being to assist the ANC beat private-sector profiteering.

Section27 was involved in all of the above in its previous form as the AIDS Law Project. More recently it lobbied for an amendment to the Competition Act that equips 7 the Commission with general market inquiry power. This is being used 8 in the first instance to investigate the private healthcare industry. In addition Section27 has recently seen progress 9 in its efforts to overturn blanket refusals by private insurance industry players to provide insurance cover for HIV positive people. It continues to make efforts to bring down the costs of dental and health care,10 and to democratise the granting of medicines patents.11

Cronin might object that he was principally questioning the record of the “rights-based campaigning model of the TAC in other sectors”.

The work of the Social Justice Coalition in exposing the Mshengu Services company 12 for not honouring its contract 13 with the City of Cape Town to service toilets in Khayelitsha, has received very wide publicity. The embarrassed City has in response announced a roll-out of portable flush toilets to “eradicate” the bucket system.

Equal Education has picketed, and engaged with, the Publishers’ Association of South Africa to urge a reduction in the price of books 14 for school libraries. In 2011 EE won an Advertising Standards Authority ruling against Patrick Holford 15 for a bogus product he claimed would boost kids’ brains. Recently EE supported the Gauteng Government in the Rivonia Primary School case 16 hoping to curb the privatisation of former model-C schools by subjecting their powers to set admissions policies to state oversight. EE keeps a watchful eye 17 on the small but hungry schooling-for-profit industry, however since 95% of children in South Africa attend public schools the work is of necessity focussed on government.

Cronin’s accusation of “one-sidedness” is without foundation. The notion that the progressive social justice movements are fixated on government, and ignore the ultimate engine of inequality, which resides in our economic system, is baseless.

Cronin is correct that “it would be entirely unfair to suggest that ‘civil society’ funding of NGOs is the reason why Heywood’s ‘civil society’ activism is ‘forced’ to focus on government.”

But this begs the question: whereas all the organisations discussed above disclose their funders on their websites, who funds the SACP?

And what reason is there that the SACP has made such a comparably unimpressive contribution to tackling both private-sector, and government, greed and corruption?

Doron Isaacs is Deputy General Secretary of Equal Education. Follow him on Twitter @doronisaacs.

References

-

Jeremy Cronin ‘Just how civil is civil society?’ Umsebenzi Online 18 April 2013 ↩

-

Harvard School of Public Health ‘Researchers estimate lives lost due to delay in antiretroviral drug use for HIV/AIDS in South Africa’ and Nattrass, N. AIDS and the Scientific Governance of Medicine in Post-Apartheid South Africa. African Affairs 2008 107(427):157-176. http://www.yale.edu/macmillan/apartheid/nattrassp2.pdf ↩

-

Mark Heywood ‘The state we’re in: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ ↩

-

Jara was the first Chairperson of TAC. At one time he was a senior member of the SACP. Jara’s confrontation with the leadership of the SACP led to his suspension from the party in December 2006. ↩

-

TAC shot at in Queenstown 2005, YouTube ↩

-

www.tac.org.za/news/tac-asks-supreme-court-appeal-consider-public-health-patent-dispute-over-cancer-medicine ↩

-

www.section27.org.za/2013/03/12/section27-statement-on-the-promulgation-of-provisions-of-the-competition-amendment-act-2009/ ↩

-

www.section27.org.za/2013/05/09/section27-and-tac-welcome-the-announcement-of-a-market-inquiry-into-private-healthcare/ ↩

-

www.section27.org.za/2013/05/21/re-statement-a-step-closer-to-eliminating-insurance-discrimination-against-people-living-with-hiv/ ↩

-

www.section27.org.za/2013/04/03/section27s-submission-to-the-health-profession-council-of-south-africa-on-guideline-tariffs-for-medical-and-dental-services/ ↩

-

www.section27.org.za/2013/04/03/report-civil-society-meeting-medicines-patent-pool-mpp-and-voluntary-license/ ↩

-

Social Justice Coalition ‘REPORT OF THE KHAYELITSHA ‘MSHENGU’ TOILET SOCIAL AUDIT’ 22-27 APRIL 2013 ↩

-

Contract between Mshengu and City of Cape Town www.sjc.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Contract-between-Mshengu-and-City.pdf ↩

-

www.equaleducation.org.za/sites/default/files/MEMORANDUM%2030%20JULY%202010.pdf ↩

-

www.equaleducation.org.za/campaigns/legal/holford-complaint ↩

-

Doron Isaacs & Lisa Draga ‘Equal education is a basic right’ The Star 9 May 2013 ↩

-

Doron Isaacs ‘Why is the Public Investment Corporation bankrolling private education for the rich?’ GroundUp 17 October 2012] ↩

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.