Equality Court orders shop to accommodate wheelchairs

“I want to give my son as full a life as I can, even if it means fighting so he can go to the shop like anyone else” says mother

The Equality Court has ruled that the owner of a Mitchells Plain superette’s policy of denying people with prams or wheelchairs access to his store is discriminatory.

He was ordered to make his store more accessible and donate money to Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital and the applicant in the case.

“The Equality Court reinforces the legal obligation on everyone to eliminate obstacles that unfairly limit or restrict people with disabilities from enjoying equal opportunities,” said Magistrate Rene Hindley.

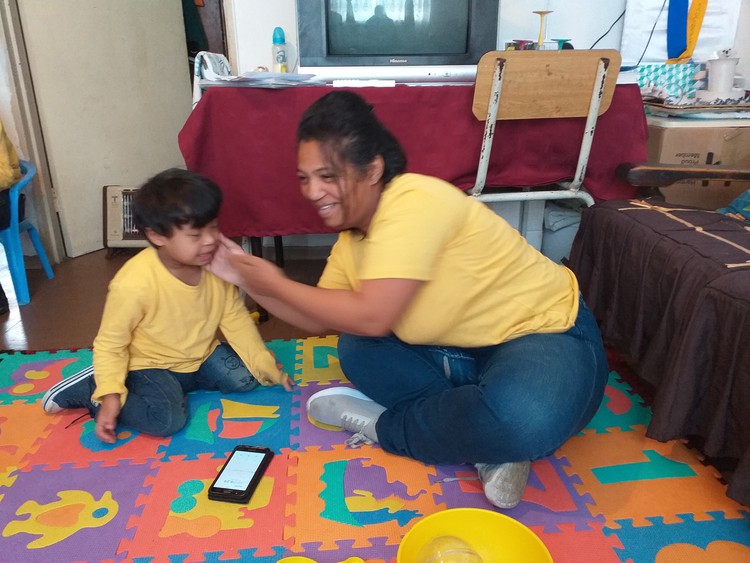

She was presiding over the matter against shop owner Salauddin Khan after his shop attendant denied five-year-old Connor Haskin, who uses a wheelchair, and his mother, Liezel Haskin, access to the store in April 2019.

Connor has Down Syndrome and some developmental delays associated with West Syndrome. He cannot walk or communicate like most children his age and needs around the clock care.

Before reading out her judgment on Friday, Magistrate Hindley told the court that lawyer Thariq Orrie had withdrawn his services and said he would no longer represent Khan.

Hindley said she had considered whether the refusal by Khan’s employee to allow Haskin and Connor access to the shop on the basis of its blanket ban on prams, unfairly discriminated against them on the grounds of Connor’s disability.

“Haskin and Connor were denied access … The court accepts that a prima facie case of discrimination on the grounds of disability has been made out. Khan has expressed to the court through his attorney that he is sympathetic to Haskin’s plight and that he employed the policy not only to limit theft but also to keep his clients safe,” she said.

Hindley then quoted from a Constitutional Court ruling in the matter of MEC for Education KwaZulu-Natal vs Pillay 2008 which read:

“Fairness requires reasonable accommodation. Reasonable accommodation is most appropriate where discrimination arising from a rule or a practise that is neutral on the face of it and is designed to serve a valuable purpose but which nevertheless has a marginalising affect on certain portions of society … Sometimes the community, whether it is the state, an employer or school, must take measures and possibly incur additional hardship or expense in order to allow all people to participate and enjoy all their rights, equally. It ensures that we do not [relegate] people to the margins of society because they do not and cannot conform to certain social norms. Disabled people are often unable to access or participate in public or private life because the means to do so are designed for able-bodied people. The result is that disabled people can without positive action easily be pushed to the margins of society.”

Hindley said it was clear that the ban on prams denied Haskin and Connor access to the store. She added that the alternatives provided by Khan were “impractical and unreasonable”.

“They fall far short of removing this barrier. Connor is not only physically disabled, he is mentally impaired and would not have been able to communicate with any shop attendant should he be left with one. And at a weight of 15 kilograms, he is simply too heavy to carry around in the store,” she said. “The effect of Khan’s conduct creates and perpetuates a system that is disadvantageous to people with a disability. Khan wanted to justify this by placing his commercial interests above his legal duty of reasonable accommodation.”

Khan was ordered to remove the sign prohibiting prams and wheelchairs and to rearrange his store in a way that it will accommodate the use of these devices, to within three months pay R5,000 to Red Cross Children’s Hospital, pay Hakin R5,000 towards Connor’s next buggy and to apologise in writing to Haskin. He also has to pay legal costs.

Outside court, Haskin said she was relieved that the matter had been finalised. “It was never about money. I made a promise to God when Connor was very sick in hospital that if He gave him back to me, I would never let anyone disrespect him. Like I said before, I want to give Connor as full a life as I can. Even if it means fighting so he can go to the shop like anyone else,” she said.

© 2020 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.