What’s causing Cape Town’s water crisis?

Population growth, drought and climate change threaten the city’s water supply

There are several likely causes of Cape Town’s water shortage. GroundUp spoke to Kevin Winter, a lecturer in Environmental and Geographical Sciences at the University of Cape Town, who helped us get to the root of the problem (we take sole responsibility for any errors).

This is part two of a GroundUp special series on Cape Town’s water crisis.

Population growing faster than storage

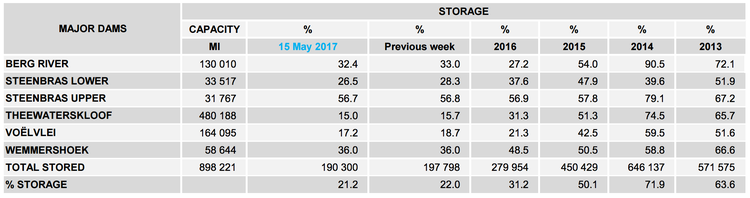

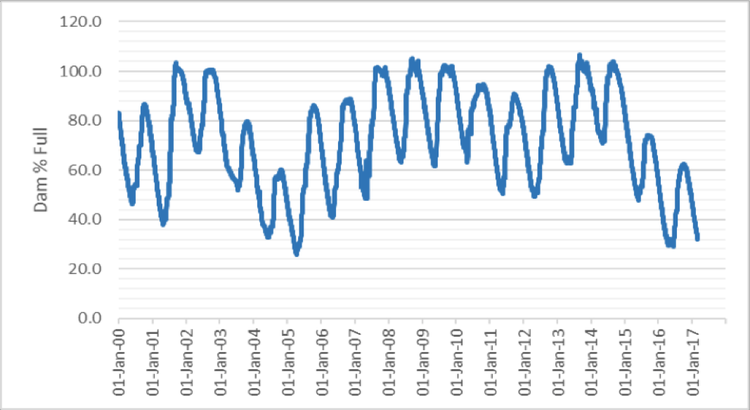

Since 1995 the city’s population has grown 79%, from about 2.4 million to an expected 4.3 million in 2018. Over the same period dam storage has increased by only 15%.

The Berg River Dam, which began storing water in 2007, has been Cape Town’s only significant addition to water storage infrastructure since 1995. It’s 130,000 megalitre capacity is over 14% of the 898,000 megalitres that can be held in Cape Town’s large dams. Had it not been for good water consumption management by the City, the current crisis could have hit much earlier.

Possibly high consumption preceding current drought

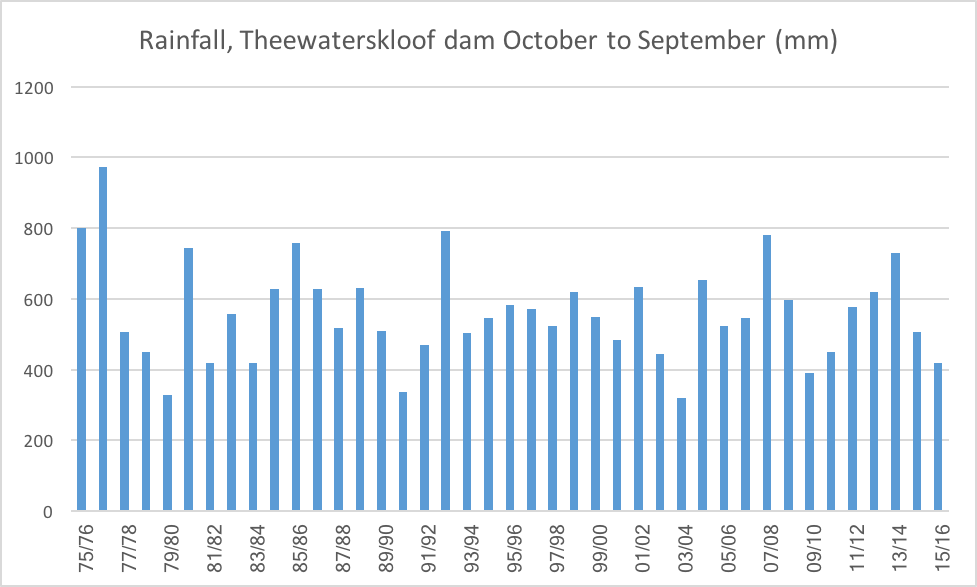

Cape Town is in the middle of a drought. The graph below shows the decreased rainfall in the past two years for Theewaterskloof, the dam supplying more than half our water.

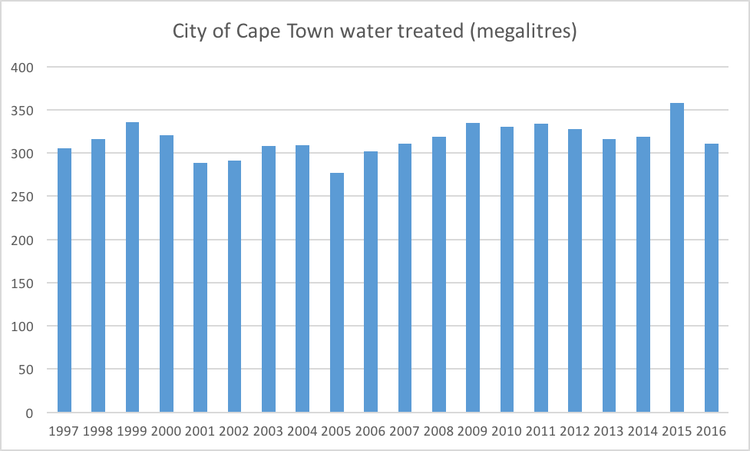

The City would not provide us with historical consumption data. However, officials did provide us with the amount of water treated. Note than in 2015 there was a spike in the amount of water treated. This suggests that consumption went up in that year, coupled with the onset of below average rainfall. However, Winter has cautioned that we can’t draw too much from this graph, because the correlation between water treated and consumed is not clear.

Climate change due to human-caused global warming

Winter explained that rainfall to the city’s catchment areas is coming later, dropping more erratically, and often missing the catchments altogether. “We have to acknowledge that carbon dioxide is finding its way into the atmosphere and has reached a new high,” he said. “This is a global system, so the bigger systems are beginning to impact us … there is no doubt that pressure and temperature are related. So disturb the temperature, you disturb the pressure and you start to see different systems operating.”

“Weather variability is suggesting two things to us. One is that the drought interval [the period between less than average rainfall years] is closing and that’s massively problematic if you can’t get a couple of good years to bring yourself back up,” Winter said. “[The other is that rainfall is] coming later. … We don’t get a sweep of cold fronts that are here for two or three days and drop the annual rainfall in nice, neat little batches. That’s no longer true.”

What this means is that we shouldn’t see the current water crisis as a temporary phenomenon that will resolve in a year or two. It’s a long-term problem. We will need substantial government intervention to make Cape Town’s water supply sustainable.

CORRECTION: The article originally incorrectly calculated population growth in the second paragraph. Thank you to reader Kane Croudace for pointing this out.

Next: Panic buying and violent protests after power failure in Port Elizabeth

Previous: Protesters demand secret ballot for Zuma

Letters

Dear Editor

Rain water must be used to flush toilets. All new developments and homes must operate on the same premise. increasing water tariffs is pointless as money cannot buy water.

Dear Editor

This article shows clearly that Cape Town's rulers have been ignoring all the warning signs that a serious water crisis was just around the corner unless drastic action was taken. The obvious remedy with the sea right there was desalination, but nothing has been done about this. And now, when I ask Mayor Patrica de Lille what the City plans to do if the dams run dry, she replies words to the effect "We don't expect that to happen." It's this hoping for the best instead of planning for the worst that looks ominously like having us fighting for a drop at street corner water tankers, even though nobody seems to know where the water will come from.

Dear Editor

Other than electricity supplies, is there anything more serious than a major water crisis for any inhabited area of a country?

Water is vital to keep humans and the whole spectrum of animals, large and small, alive. Also to maintain vegetation, apart from certain plants and trees which can put their roots down the water table to maintain life. Always providing that the water down there is not too contaminated, primarily with salt. But plants are essential to maintaining life, whether they are eaten after being cut from plantations and in many cases cooked or eaten as meat from animals bred for this purpose.

And here we now have the result of an extended drought in the Western Cape, with seemingly no consideration being given by the CT City Council for a situation which specialists at UCT and other academic institutions have been giving warnings for a number of years, as we read in press statements, radio and TV programmes - a predicted fall in vital rain.

It is a great pity that there is still resistance to the fact that modern populations in developed countries predominate in urban areas, where there are commercial and small to large industrial manufacturing enterprises, as opposed to rural agricultural areas. Even President Zuma has been complaining that the majority of people seeking compensation for land stolen from their antecedents in earlier times do not want land back - except maybe enough for a personal plot on which one's home is built - but prefer financial compensation. Does anyone really need to ask the question: where are the small minority of farmers, why do they prefer very large areas to farm? Areas which require trained individuals to run and grow their crops efficiently, with all the necessary equipment for their purposes, and staffed by the relevant small number of people who really do like working on the land. Why is it such a difficult point to understand?

So we have a water crisis, magnified by the large increase in the urban population.

Dear Editor

Domestic rainwater storage can go a long way to helping with the situation mentioned in the “What’s causing Cape Town’s water crisis?” article. For example, I lived in Western Australia for three years and existed solely on harvested rainwater. All new builds should be supplied with such storage where expected rainfall warrants this step. Even if the water is only used for flushing the toilet, this would make a considerable contribution.

In the meantime, up on the hills of our Western Cape catchment areas, we should be looking at potential for developing wetlands. The water is there but is often lost as it just dribbles down to the sea - if it hits dams these suffer from excessive silting and loss of depth and capacity - losing depth results in higher water temps etc.

Would it be cheaper in the long run to divert water from the big dams on the Orange River to the Cape instead of desalination? The human race pumps oil over vast distances, why not water!

None of the above steps are cheap, but if we don't take them the only people to gain from the drought will be undertakers and crematorium operators - do you really want to see these guys getting rich?

Dear Editor

Putting aside the main reason for the water shortage, massive population growth, here is one of the most important concerns that is not being raised:

If we look at the rainfall of our catchment areas, then we see there have been bigger droughts in the near past, and yet our rivers are not flowing as strongly as they used to. Why is that? Nobody is looking at the state of our rivers. One thing that is clear is that our rain has become more sporadic. This can easily be due to our mountain fires. Less vegetation and a shock to the system equals more sporadic rainfall. Vegetation is also required to catch the rain and release it steadily into our rivers. There are a few projects that are currently being carried out around the world where desert/desolate areas are being re-vegetated and after a while rivers that have been dry for ages start flowing again.

Then the big concern. Due to all the water greed in storing as much water as possible in our dams, our rivers are not completing their cycles, they are not reaching the ocean. Now we learn about this cycle in school (The Water Cycle): The river water reaches the ocean and then clouds get formed and it brings rains again to feed the river, without completing the cycle. The river starts essentially dying. There should be laws put in place to set a minimum percentage of how much water should be allowed to flow from the dam in order to keep it alive. This should be done scientifically to find a balance. How much wildlife has been destroyed due to our rivers not flowing. There is currently a movement in India (Rally for Rivers) to try and save their rivers, because they are sitting with the exact same problem. Their rivers aren't completing their cycles due to excessive damming, and now their rivers are drying up. Now, many will say that we can't let some of our dam water go, for the greater good, but what use is there having a dam but no river.

Dear Editor

Has the Western Cape Government ever considered making it compulsory that every household must have water containers on the premises to hold all grey water and catch rainwater, should we get rain? Have they ever considered subsidising these containers or donating one for every household?

Would that not solve part of the problem in the short term and be a solution for the future when the cycle of this dreadful drought eventually breaks? What is the Western Cape Government doing with the water that is pumping out the mountain and down into Camps Bay at a force of what seems like a 1000L/sec. It looks like it is just going straight into the sea!

Why is there no infrastructure to take this water into our dams or will this deface the mountain and spoil it for the rich in Camps Bay and tourists?

Dear Editor

I don't normally write in public forums, but into the fray I stray! I would like to make a few observations about ground water and the effect of increasing coverage of invasive alien species on the amount of water that is supposed to run into dams in the first place. I have witnessed a beautiful mountain stream go dry over a period of weeks, last December 2016. This was in the middle of summer, not much rain. One night a fire wiped out about 100% invasive trees from the mountain side catchment area. 12 hours later the fresh spring was running again and hasn't stopped since (+- 4 litres per second). The increase in flow had NOTHING to do with rain, but the reduction of alien vegetation that is taking up to 30-40% of what should running into our catchment dams. Working For Water did not work at all!

Secondly, I live in the mountains. We used to have a lot of snow every winter. Theewaterskloof Dam was essentially designed to catch the snow melts every winter and NOT rain water! It was also built to provide water for agriculture and not the "City" so to speak.The streams that feed the dam currently were never going to fill it on rain alone. Snow melt was the primary function of her design. Having said that, She took 5 years to fill ( with snow melt) with no water being used at all. So.... 100ml of rain for 7-9 days straight will only increase Her by about 5%. But with water being 'taken' out all the time, we are trying to fill a bucket but with a large gaping hole in it.

She may never fill again.

I do believe that all the other factors mentioned in your articles to be valid, however Cape Towns water crisis is also about technocrats trying to pull rabbits out of hats, and not really about common sense reasons (solutions) for cause and effect. Politicians should never try to fix broken pipes, and plumbers should not write the law. Right now, the Governing Party of the W.C has valiantly decided to alienate and essentially attack it's own constituents, instead of washing clean with it's voters and ask for their help. May the water be with you!

Dear Editor

I'm a visitor to Cape Town. I come from a water-rich country, Canada, and have lived in drought-stricken Southern California for the last several years. I'm in awe of how Capetonians have banded together to save water. But why is no one here talking about the fact that the majority of a human's water use is invisible?

Yes, not flushing and short showers will save water in the immediate term, but your weekly braai tradition must be revamped if your country is going to survive this water crisis. It takes 15,000 litres of water to produce 1kg of beef.

For a long-term solution to this crisis that will only get worse as the years go by, South Africans must reconsider their diets. And no, I'm not saying you should all be vegetarians, but if you cut down your meat consumption you'll be saving much more water than by not flushing!

This isn't mentioned on any government website or news article I've encountered in the two months I've been here. Choose grass-fed lamb instead of corn-fed beef. Bring more veggies to your next braai and discuss this with your friends! Talk about how to help farmers transition and how to pressure the national government to revise agricultural water allocations.

I know everyone's in a state of panic because the taps will run dry, but please don't forget this is a long-term problem that requires far more than buckets in the shower.

Dear Editor

I have five blue water tanks at home which I installed last winter for storing water from rainfall and washing machine water which gets use for grey water to my cisterns and other things.

Why can't the City of Cape Town have a plan in place to supply people with one or two 210 litre drums for storing water?

Suddenly plastic container prices have sky rocketed from suppliers and ripping the people off. I suggest that the government or local municipalities look into this matter.

Dear Editor

There is so much evidence showing the City of Cape Town has been aware of this problem way before they decided to take action.

When Israel became a state, most of their land was desert. And if we see pictures today, it has been transformed to a view which doesn't show that it was a desert. It's doing so well, it has even started to grow grapes for wine making. I just cannot believe that no one is looking to other nations for assistance.

I remember being at the Castle in the City. That day the moat around the castle was empty due to renovations. I heard about the water crisis and when I was back to town, I noticed they filled the entire moat with water. The parks had their fountains running even after they said they switching it off.

We all have a part to play but if climate change is real and we have an influx of people from other provinces coming for better opportunities, then our Local Government failed to plan ahead.

I do hope we get through this summer with water but it looks doubtful.

Dear Editor

The statistics do not prove any positive correlation between water consumption and water treatment.

The data only proves that water has been over treated; or treated at a higher treatment to consumption ratio. This means that the management of water in Cape Town has in the long term been rather poor and not “good” as you describe it.

Hence you referring to ‘good water consumption management’ is rather a sweeping statement, and unwarranted by any statistical facts in the article.

© 2017 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.